A common myth associated with adventure travel is that it only includes extreme activities like caving, heli-skiing, and rock climbing. While activities like this are certainly one aspect, adventure travel encompasses a full range of activities and itineraries from wildlife safaris to participation in cultural events. Adventure travelers, too, represent a range of identities, ages and physical abilities. Regardless of activity type, the often physical nature of adventure travel makes accessibility an essential topic for adventure travel professionals to understand and address.

Accessible design solutions should be a consideration for all adventure travel professionals — not just business owners, human resources professionals, dedicated staff or as part of a compliance routine. From destination development to itinerary planning, designing for accessibility requires the examination of the small, everyday, and often overlooked decisions that either raise or lower the barrier to participation.

Mismatch

It’s common to think of disability as a personal health condition, but Kat Holmes, author of Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design, invites us to think about disability as a mismatched interaction. “Examples [of mismatch] are all around us. It’s the reason a child climbs onto the counter to wash their hands at a sink. It’s why people are left searching for instructions on how to navigate a software application when it’s updated with new features. Anyone who’s tried to order lunch off a menu that’s written in a language they don’t understand is in the middle of a mismatched interaction.”

Whether it's a right-handed computer mouse for a left-handed person, a cash-only or card-only restaurant, an item placed too high on a store’s shelf, or a menu without dietary options, everyone has experienced a mismatched interaction to some degree. “The objects and people around us influence our ability to participate," writes Holmes. "Our cities, workplaces, technologies, even our interactions with people are touchpoints for accessing the world around us. Sometimes we can interact easily, sometimes we can’t.”

Design decisions

In order to shift the paradigm, we have to move away from seeing disability as a personal health condition and move toward addressing disability as a series of mismatched interactions. “A mismatched interaction between a person and their environment is a function of design,” says Holmes. “Change the environment, not the body. For people who design and develop products, every choice we make either raises or lowers these [barriers to participation].” To improve accessibility, we have to change the design decisions that we have the power to make.

"Disability is now understood to be a human rights issue. People are disabled by society, not just by their bodies. These barriers can be overcome, if governments, non-governmental organizations, professionals, and people with disabilities and their families work together.” — World Health Organization (WHO).

If we start thinking about accessibility in adventure travel through the lens of design decisions, then we must identify the designers. A designer is simply, and in a sense, anyone who has ever solved a problem. Design decisions are not only made by the company owner or executive team — we all have the power to make decisions and design changes. From small, everyday operational decisions to travel product development, addressing mismatched interactions should be an integral part of the decision-making process.

Accessible tourism and an aging population

In recent years, people with disabilities have contributed more to the travel industry than ever before, becoming a sector with tremendous potential for growth. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are 1 billion persons with disabilities in the world, which means that 15% of the population has a physical, mental or sensory disability. Accessible tourism is a significant market opportunity for the tourism sector — not just due to increased participation of people with disabilities, but with the increased participation of the aging population as well.

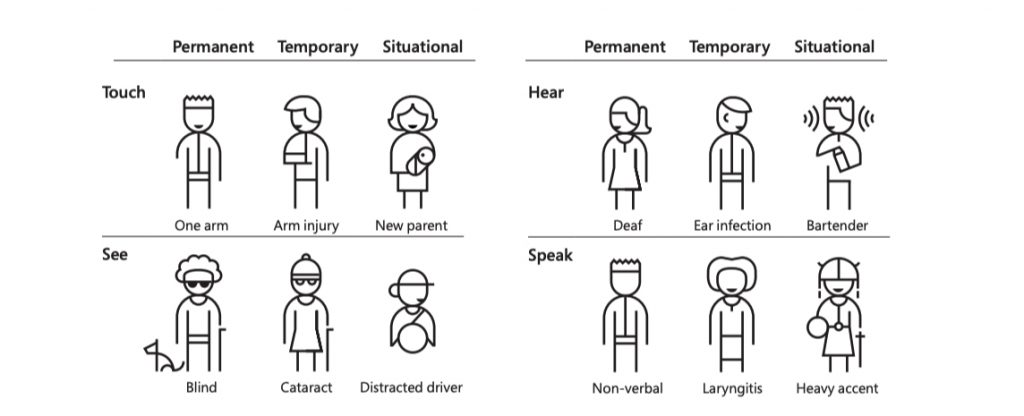

When you design for disability, you can also accommodate the aging population. According to the University of Technology, Sydney, if the barriers faced by people with disabilities are addressed, the barriers for older population groups also lessen. Designing for one group and extending to many is called the flow-on effect. According to the Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 30% of a population will have access requirements at any point in time. Whether a disability is temporary, situational or permanent, most people will experience disability at some stage in their life. With this in mind, let’s look at the flow-on effect and other inclusive design principles to learn how to design for inclusion with decisions you make daily in your organization.

Flow-on effect (design for one, extend to many)

In the illustration of the flow-on effect above, you can see that a design solution for someone with a permanent disability can also work for someone with a temporary or situational disability. From our own research, the Adventure Travel Trade Association (ATTA) has learned that the largest sector of adventure travel tour operator clients (41%) is between the ages of 50-70. Given this flow-on effect, we can expect that designing for accessibility will have a significant positive impact on raising barriers of participation for this critical group as well.

Design with, not for

Human diversity should inform design decisions. This means we should be solving accessibilities with people experiencing a mismatch with travel products, not for them. While often well-intentioned, ‘designing for’ people presumed to be disadvantaged can lead to super hero-victim or benefactor-beneficiary mindset. Holmes warns that this mindset can lead to specialized solutions that cater to stereotypes about people.

Seeking feedback is a low-cost, low-barrier, way to start with this principle of inclusive design. As a first step, Holmes suggests identifying and building an extended community of “exclusion experts” who contribute to the design process. The exclusion experts can be identified as anyone who experiences the greatest mismatch when using your solution or product, or who might be negatively affected. Exclusion experts can be found among clients, potential clients, consultants, employees, potential employees and other existing communities. In action, “designing with, not for” means facilitating meaningful ways for exclusion experts to participate in the design process.

Recognize exclusion

To make accessibility a priority in your organization, it's imperative to recognize and address mismatches and exclusion. Don’t accept the status quo, involve people with disabilities and work together to find a solution. Tour guides and staff that work directly with clients are some of the best resources and advocates. If you see something, if you witness a mismatch, say something. Bring it up to your company to make accessibility a priority. We have to extend the concept of designer, understand that disability is a function of design, and that all travel professionals have the power to shape design decisions.

As you begin to prioritize accessibility and start to incorporate the principles of inclusive design, you will likely experience some apprehension and challenges associated with accessibility work. Holmes addresses three common fears in her book. First, she explains people are often afraid to say the wrong thing, use the wrong terminology, or offend someone, which can lead people to avoid the topic all together. “Inclusion isn’t nice. It’s challenging the status quo and fighting for hard won victories. The opportunity is to be clear and rigorously improve our lexicon for inclusion.” Holmes reminds us that it’s easy to mistake nice words for good intentions, just as it is easy to chastise someone who is committed to inclusion but uses the wrong words. Holmes says asking questions, and then simply listening, is often the most courageous way to start.

Play the long game

You will never design a solution that works for everyone all the time. It’s normal to fear “getting it wrong,” and it’s likely you will at some point in the design process. “Inclusion is imperfect and requires humility," writes Holmes. "It’s an opportunity to be curious and approach challenges with a desire to learn.” Don’t let perfect solutions stand in the way of effective solutions.

Finally, inclusion is ongoing. Holmes reminds us, “There are rarely enough talented people, time, and money to make a sudden sea change in inclusivity...As a result, the work of inclusion is never done. It’s like caring for your teeth. There is no finish line. No matter how well you clean your teeth today, over time they require more care.” No one person or team has all the answers.

The key is to start paying attention and addressing mismatches — remember the goal is to change the environment, not the body. To learn more and practice inclusive design principles for accessibility in adventure travel, try using the inclusive design toolkit with your company. Start conversations, seek feedback, and grow your exclusion experts community to make sure you are designing with, and not for people with disabilities.

Footnote:

The principles of inclusive design outlined in this article are from Mismatch and Kat Holmes’ award-winning toolkit for inclusive design. Kat Holmes is the founder of mismatch.design, a design firm dedicated to inclusive design resources and education. She led Microsoft’s executive program for inclusive product innovation and currently works at Google as Director of UX Design (user experience), continuing to advance inclusive development for some of the most influential technologies in the world. While much of Holmes’ work is centered around inclusive design and technology, the principles can be easily applied to adventure travel as well.