Editor's Note: This interview originally appeared on Green Global Travel's blog. It's reprinted here with full permission.

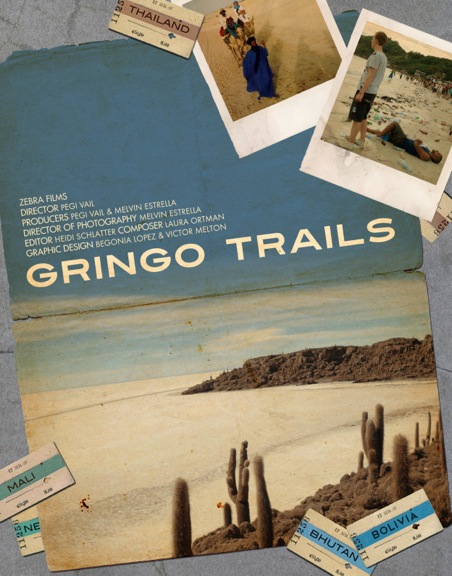

“Tourism is really about selling nature and cultural heritage,” says National Geographic Traveler editor Costas Christ during an interview near the beginning of the Gringo Trails documentary. The rest of the thought-provoking film explores the obvious follow-up question: At what cost?

The film was directed and co-produced by Pegi Vail, an American anthropologist and Associate Director of the Center for Media, Culture, and History at NYU. Once an avid backpacker herself, Vail began the project back in 1999 as a Fulbright scholar researching the impact of backpacking on the Salar de Uyuni region of Bolivia. Over time, the film’s focus morphed into more of a big picture examination of the impact mass tourism has on the culture and environment of a destination.

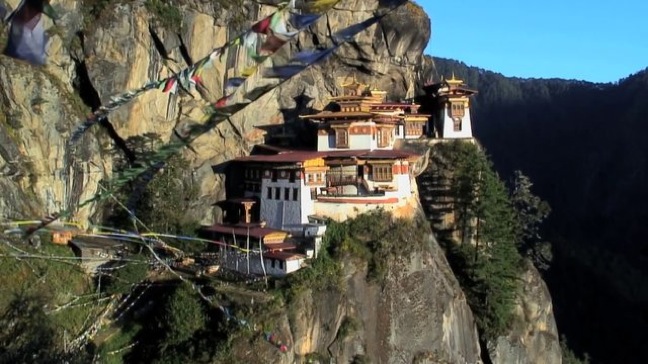

Through interviews with eco-lodge operators, members of Bhutan’s royal family, and travel experts such as Pico Iyer and Rolf Potts, the film culls stories from all along the historic “gringo trail.” The crux of the conversation is how we can reconcile the needs of tourists who want to travel off the beaten path in search of authentic experiences, and those of developing nations desperately in need of tourism revenue, without destroying the things that make these destinations uniquely beautiful.

While Gringo Trails offers no easy answers, it does ask poignant questions and offers some compelling examples of role models for sustainable ecotourism. We recently spoke with Vail (whose book based on her research, Right of Passage, is forthcoming) to discuss her thought-provoking film in depth.

What inspired you to make Gringo Trails?

I originally started making the film in 1999. Prior to that I’d been a backpacker in my 20s and early 30s, and I felt like it was a culture that should be looked at. I was hired to do my own research as an anthropologist on my own tribe– travelers. I wanted to come to the film through two different perspectives, as both a participant and observer. I put the film aside and came back to it in 2009-2010. By then it had changed based on my own research in Bolivia, and seeing what I thought had become the more important story, which were these gradual changes that we could see through filming these different time periods. The environmental and cultural impact became the more important story to tell, because the travel industry had become so huge around the world.

What was the most surprising thing you learned over the course of making the film?

We, as travelers– and I include myself in that– aren’t aware of how privileged we are to be able to travel the world and experience all of these different cultures and places. If we recognize that privilege, then we will become more responsible travelers.

Can you talk about why you chose to focus on backpackers instead of, say, luxury travelers, and the types of damage backpackers are doing when they travel to these previously unspoiled places?

There are obviously some people who are doing things more responsibly than others. Now that we have more people traveling– more backpackers as well as mid-budget and upper-budget traveling– you’re going to see more damage in all these arenas. But backpackers tend to spend more time in a place, and will potentially become part of communities and spend money locally. So they have the potential to make more of a positive impact with responsible travel choices.

Budget travelers trying to get the most out of every penny in developing nations will haggle to get the lowest price. Some consider that a selfish thing: They’re getting to explore the local community at rock-bottom prices, when the impoverished community desperately needs more revenue.

I totally agree. There are definitely negotiations involved, learning what things are worth. But, knowing that you, the traveler, make more money, of course you’re going to be looked at as having a bigger wallet. Even if you’re traveling on a shoestring budget, you’re still likely coming from a middle-class to upper-middle class background.

It bothers me when I hear travelers complaining that it costs $30 for tourists to see a UNESCO World Heritage Site like Angkor Wat, while locals only pay $6 for admission. To me it shows a serious lack of perspective regarding the wealth disparity in the world.

Yes, because the locals don’t have that money. But those travelers will spend that same money on beer in a second!

In terms of my research, I did a large survey of how much time backpackers spend on the ground. On average, they spend at least 85% of their time with other travelers [rather than locals], which is pretty high. Sometimes travelers don’t know how to get to know local communities, so their main interactions tend to be in the marketplace.

We had a scene in the film that got cut, where there were four travelers– a Dutch, American, Peruvian and Australian– all traveling together. We were at a Bolivian market, and the American got to haggling over 10-15 cents for breakfast. It got ridiculous, and the Peruvian and Australian travelers were getting really embarrassed and uncomfortable. But the Dutch traveler says, “No, it’s the principle!” To me, it was very telling of this idea that it makes us feel more authentic somehow to pay exactly what local people do.

One of the most interesting things you talk about in Gringo Trails is the backpackers’ herd mentality. There’s a line that struck me: “Don’t tell anyone about Haad Rin Beach, because backpackers will end up going there.” How does that herd mentality lead to negative consequences?

People think that guidebooks aren’t “institutionalized tourism.” But backpacker tourism is, in some ways. It begins through word-of-mouth about an off-the-beaten-path place. Then more people come, and of course it ends up in a guidebook. It’s very similar to the gentrification process. I look at my own neighborhood, where artists moved into a working-class neighborhood in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Backpackers and artists pave the way for these places, but then they tell other people, and more people come. I think it’s time to let some places breathe. If you hear that too many people are going somewhere, go someplace else.

But whose responsibility is it to limit the impact tourism can have on a place? The government regulatory commissions? The tour operators? The tourists? Where does the responsibility for making conscious, sustainable decisions lie?

It’s all of the above. Travelers need to be more responsible and recognize that they can’t have everything and do everything they want. Tour operators need to say, “We don’t offer this sort of [irresponsible] travel experience.” There’s a good example in the film: In the salt flats of Bolivia, the guides used to bring snakes and put them around people’s necks, and the tourists would touch them. Some travelers would say, “I paid all this money; I deserve to do this!” But there was an awareness campaign mounted that educated people about how damaging bug repellent, which can be toxic to the snake, has been to the local anaconda population. There’s been a change with the number of tourists coming in and handling animals.

What choices do you see that travelers can make to positively impact destinations they travel to?

Do your research ahead of time. It costs nothing to go online and read about the cultural norms of a place. Most places in the world have Internet access now, so try to read about cultures through the perspectives of indigenous writers. Learn about the best sustainable tourism initiatives that you can support, and know that you’re going to find them more culturally and environmentally true to these places.

Blogs seem to be the travel guidebooks of the 21st century. What role do you see bloggers playing in the problems outlined in Gringo Trails?

News travels so much faster these days. A place that’s talked about online can go viral quickly. That’s created a huge change in what I call “tourism globalization.” I think it goes back to people realizing the privilege that we have as travelers. I look back to my travels as a young person, and I didn’t even know that genocide was happening against the indigenous community in a neighboring village in Guatemala while I was there. It’s important to become more aware before you go into a culture, and understand the do’s and don’ts of a community. I think bloggers can really help with spreading that information.

– by Bret Love; all photos courtesy Icarus Films & Pegi Vail